For a developer, entering the local-first world can be disorienting; our understanding of how things normally work is often turned upside down.

That’s especially true with the question of peer-to-peer security.

At first, this seemed straightforward to me. Then I thought about it some more and it started to seem impossible. Then I thought about it a lot more, and it went back to seeming doable. But I’ve had to reconsider what we really mean, like really MEAN, when we talk about “permission” or “trust” or “identity”.

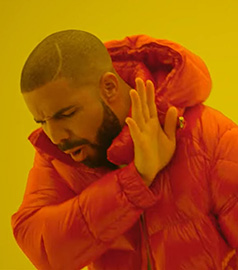

Application security generally breaks down into three areas:

- Authentication: Alice needs to be sure that messages and changes that say they come from Bob actually did come from Bob

- Authorization: Alice needs to be sure Bob can only see what he’s allowed to see, and do what he’s allowed to do

- Confidentiality: Alice and Bob need to be sure Eve can’t snoop on what they’re saying and doing

When all of your stuff is on a server, authentication and authorization are well-understood problems with lots of off-the-shelf solutions to choose from. Conceptually, it’s uncomplicated: The server acts as a gatekeeper between users and the data. If Bob can’t convince the server that he’s really Bob, well then the server won’t let him in. The server knows what Bob’s allowed to see and do, and it simply won’t let him see data he’s not allowed to see, or change it in unauthorized ways.

In practice, what this means is that we rely on well-known technology companies — Google, Apple, Microsoft, etc. — to vouch for us in our interactions with each other.

This is one of those situations that seems unremarkable until you really start thinking about it, at which point you wonder why you ended up living in this bizarro-world timeline. How is it that the role of certifying identity has fallen on consumer brands?

Perhaps it would be more logical for this role to fall on the government, or on a non-profit organization like ICANN. Or maybe there is a way for us to vouch for ourselves, instead of relying on tech giants, governments, or any centralized organization to confirm our identity.

Down the rabbit hole

When I started thinking about authentication in these terms, it seemed clear that the way forward would involve cryptography — specifically, public-key cryptography. But the details were still fuzzy.

To make this more concrete, let’s imagine we’re making an app that manages projects and tasks for a team, like Trello or Asana. But instead of relying on a server to store the application data, each person on the team has a complete replica of the data on their own computer (and on any other devices they use, like their phones); and everyone’s replicas are magically kept in sync with each other.

👩🏾 Alice will be our hypothetical superuser: She’ll set her team up with our app, and invite her team members to collaborate: 👨🏻🦲 Bob, 👳🏽♂️ Charlie, and 👴🏼 Dwight.

Let’s list some of the questions that we might have at this stage:

Permissions management

Q: Without a server to keep track of group membership and permissions, how can Alice add and remove team members, and limit what they can and can’t do? Where does that information even live?A: All changes to the group’s membership and permissions are recorded as a sequence of signed and hash-chained changes called a signature chain. Every group member keeps a complete replica of the signature chain and can validate other members’ actions independently. All authority can be traced back to the group’s founding member. Jump to details

Key management

Q: To encrypt anything or use digital signatures, you need to know each other’s public keys; but how can that happen if you don’t have a trusted, centralized key server?A: New members are invited using a Seitan token exchange, which is basically Trust on First Use (TOFU) hardened with the use of an invitation key. Jump to details

Peer authentication

Q: Without a server to vouch for his identity, how does Alice know it’s really Bob at the other end?A: We use a signature challenge: Alice creates an identity challenge document for Bob to sign, and checks his signature against his public signature key. Jump to details

Read authorization

Q: How can you keep some users from seeing sensitive information if each user has a complete copy of the data?A: We encrypt sensitive data for multiple users using lockboxes (encrypted keys). Jump to details

Write authorization

Q: How do you prevent unauthorized users from modifying things they’re not allowed to modify?A: Since all users have a full replica of the signature chain and can use it to compute the current state of the group’s membership and permissions, each user can independently determine whether or not to accept another member’s changes as valid. Jump to details

Synchronization and concurrency

Q: How does everyone stay up to date with changes to the group’s membership and permissions? What happens when two admins make concurrent changes?A: We represent the signature chain as a directed acyclic graph so that we preserve the history of any concurrent changes. Conflicting changes are resolved using “strong-remove” heuristics. Jump to details

These are all tricky problems. Some of them have fairly well-understood solutions; others are closer

to the cutting edge of academic research. I’ve spent a lot of time over the last few months trying

to understand the landscape, and to create TypeScript implementations of the best available

solutions to each piece of the puzzle. The result is a library called @localfirst/auth, which I

hope brings it all together to make it easier to create secure local-first collaboration

applications.

Let’s look at each of these in more detail.

1. Permissions management

Introducing the signature chain

Q: Without a server to keep track of group membership and permissions, how can Alice add and remove team members, and limit what they can and can’t do? Where does that information even live?

In the absence of a server, the group rules themselves have to be replicated on each client. Who’s a member, who’s not, and who’s allowed to do what — and importantly, who’s allowed to change the rules — all that information has to be shared with everyone, just like the data that the team is collaborating on. But how do you know who to trust about what the rules themselves are?

It’s not a blockchain, I swear!

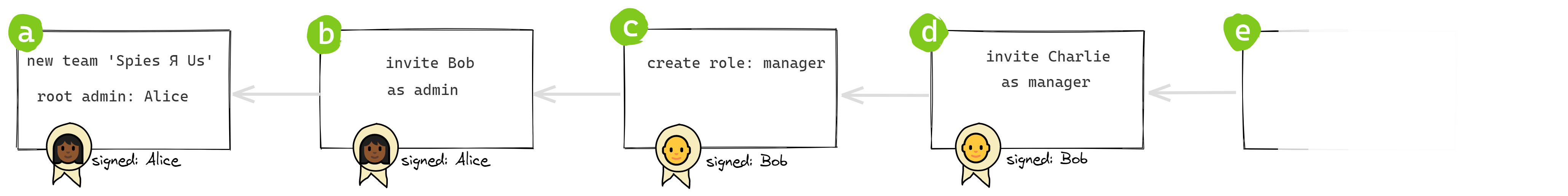

After a couple of false starts, I found a solid solution to this problem in the docs for Keybase’s Teams application: A signature chain contains a series of links, each one containing a single change to the team’s membership or roles.

The first link, the root of the chain, marks the creation of the group and by definition adds the founder to the group as an admin. It also includes the founder’s public keys.

Each subsequent link represents an administrative action such as inviting a member, removing a member, promoting a member to admin (or another role), or demoting a member.

Each link contains a cryptographic hash of the preceding link, so the order of the links cannot be altered.

Each link contains a digital signature of its content by the member making the change, so that its authenticity can be independently verified, and so that the link body cannot be tampered with.

This chain is replicated on each team member’s device, and any member can use it to reconstruct the group’s current membership and roles. Given the same chain, two members will always arrive at the same state. And given a new link, any member can independently determine whether it’s valid or not, and come to the same conclusion as every other member.

The key insight behind the signature chain is that all authority can be traced back to the group’s founding member.

When Alice creates a group, she is the group’s only member and the group’s only admin. Suppose she adds Bob, Charlie, and Dwight. Then:

- 👩🏾 Alice promotes 👨🏻🦲 Bob to admin

- 👨🏻🦲 Bob promotes 👳🏽♂️ Charlie to admin

- 👩🏾 Alice removes 👨🏻🦲 Bob

- 👳🏽♂️ Charlie removes 👴🏼 Dwight

When Charlie removes Dwight, how do I know that’s a legitimate change? Well, if I look back through the history of changes, I can see that:

- 👳🏽♂️ Charlie was an admin at the time he removed 👴🏼 Dwight

- 👳🏽♂️ Charlie was promoted to admin by 👨🏻🦲 Bob

- 👨🏻🦲 Bob was an admin at the time he promoted 👳🏽♂️ Charlie

- 👨🏻🦲 Bob was promoted by 👩🏾 Alice

- 👩🏾 Alice was an admin at the time she promoted 👨🏻🦲 Bob

- 👩🏾 Alice’s original admin rights come from having created the group

In this way we can conclude that Charlie’s admin rights are legitimate because they can ultimately be traced back to Alice.

Note that even though Bob was ultimately removed from the group, he was a member with admin rights when he promoted Charlie. His promotion of Charlie remains valid from that point forward, unless and until another admin removes or demotes Charlie.

This works the same way no matter how long ago the group was created, no matter how much turnover there is, and whether or not Alice is even a member any more.

2. Key management

Where do keys come from?

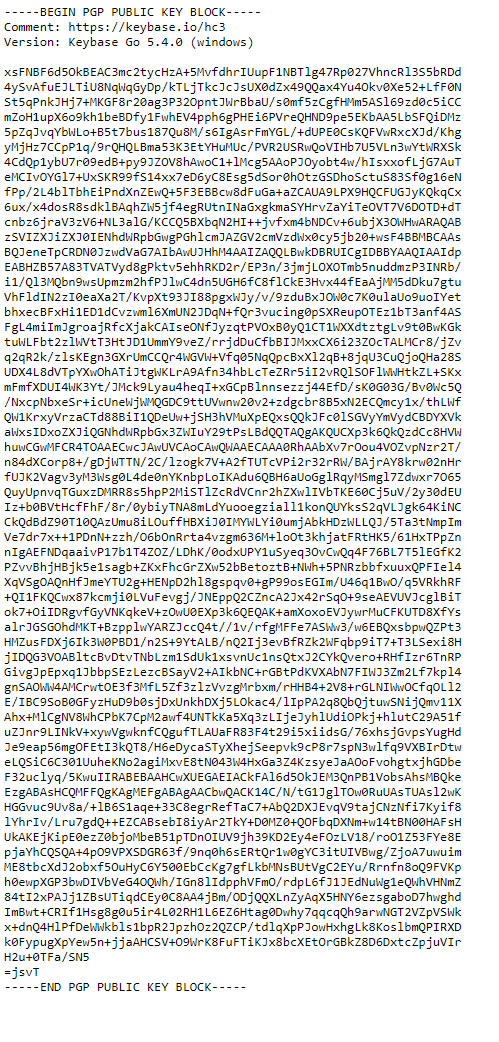

This is what my public PGP key looks like.

Q: To encrypt anything or use digital signatures, you need to know each other’s public keys; but how can that happen if you don’t have a trusted, centralized key server?

We need to talk about public keys and how we associate them with individual identities.

Remember, the great thing about public key encryption is that Alice and Bob don’t need to share a secret in order to verify each other’s signatures or encrypt messages for each other: they just need to know each other’s public keys.

So how does Alice find out what Bob‘s public key is? For that matter, how does Alice even know what her own public key is? Where does one get one of these keypairs anyway?

The problem of linking identities to public keys — known as the public key infrastructure (PKI) problem — doesn’t seem like it should be a show-stopper, but it’s been one of the biggest obstacles to widespread adoption of encryption.

The most obvious solution is to have some trusted party keep a directory of people and their public

keys, and that’s totally a thing that exists. The certificate authorities (CAs) that make secure

https connections possible are an example: The SSL certificates that they issue are just documents

that link a domain to a public key, digitally signed by the CA. (Browsers and operating systems come

with a set of trusted CAs’ public keys built-in.)

Some big companies have their own certificate authorities to give employees unfalsifiable digital identities. Some governments do the same for citizens and residents: Here in Spain, I was issued a certificate to install in my browser, which allows me to transparently authenticate to government websites and sign official documents digitally.

But we’re trying to do this without depending on centralized services.

A decentralized solution might be for people to actively share their own keys directly with each other. This was the approach taken by PGP (‘Pretty Good Privacy’), the first encryption toolset intended for ordinary users, in the 1990s. People would put their public keys on their websites and in their email signatures. Apparently there were key signing parties where people exchanged and signed each other’s keys.

This approach required a lot of in-person interaction, and it was all just too geeky and weird. I would estimate that approximately 100% of the population has never attended a key signing party, so we’re going to need an alternative approach.

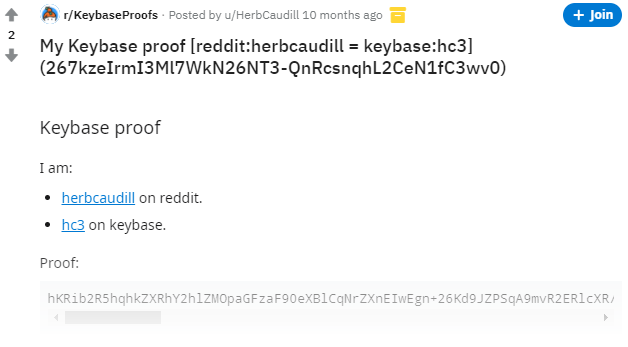

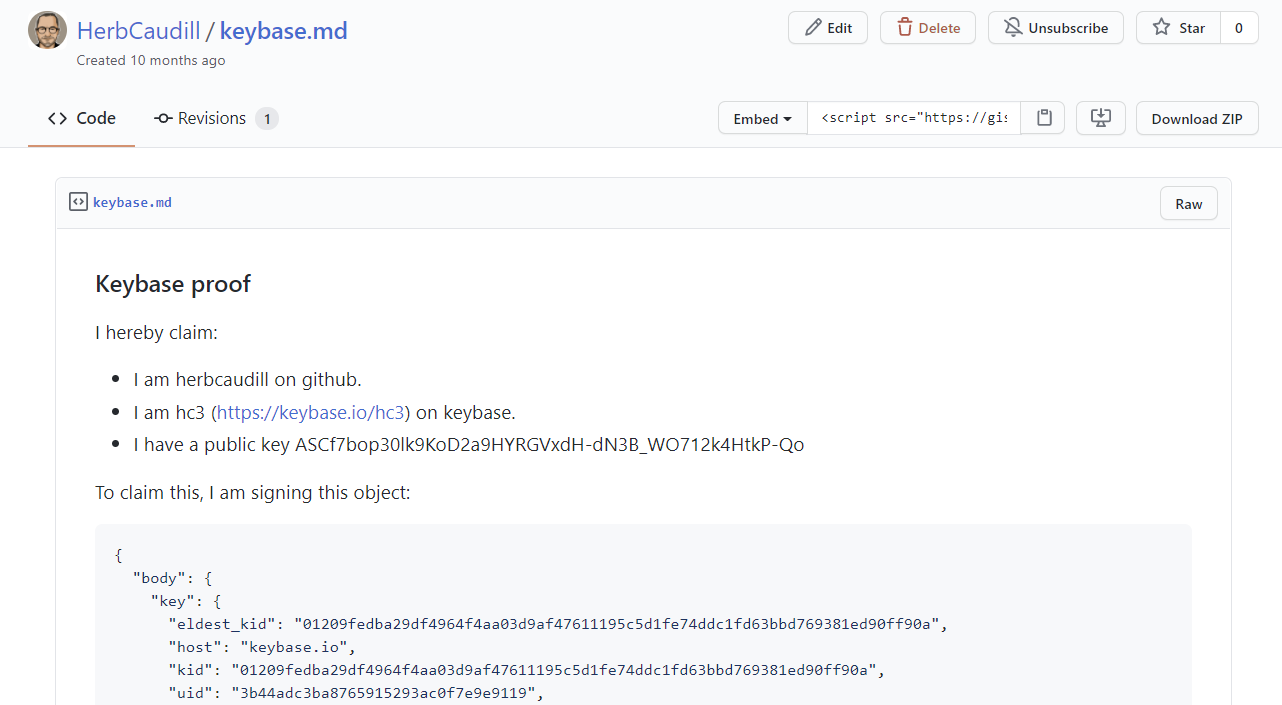

Keybase had the clever idea of getting people to associate their public keys with their identities on public sites where they have accounts, like Twitter or GitHub.

I’ve used Keybase to “verify myself” by posting machine-readable statements on Twitter, GitHub, and Reddit

It’s a clever idea. When Keybase originally came on the scene, everyone who reads Hacker News immediately signed up and tweeted their public keys. The remaining 99.9% of planet reacted by not doing anything at all, and we all proceeded to live our lives exactly as before without ever thinking about Keybase again, except briefly when Zoom bought the company in the early days of the pandemic in a desperate effort to quickly shore up their own security cred.

What PGP got wrong

What sets apart the current crop of secure messaging apps — apps like WhatsApp or Telegram or Signal, which were the first to bring end-to-end encryption to the masses — is that they make encryption transparent to the user.

It’s not just that people are scared off by keys that looks like screenfuls of gobbledygook. Fundamentally, PGP failed because it required “our” keys to become stable components of our digital identities, like our email addresses or our telephone numbers, that we managed ourselves.

But encryption keys are fundamentally not friendly to humans. They’re too long to memorize, unless you’re a savant or a circus act. Retyping them is tedious and error-prone. If it’s up to us to store them, we’ll probably either put them somewhere where we’ll never find them again, or somewhere insecure, or both.

A more appealing idea is not to not think about our keys at all. As Peter Van Hardenberg, CEO of the Ink & Switch research lab, has said to me more than once: “If the user sees an encryption key, you’ve already lost.”

Here’s a summary of the differences between these two different ways of thinking about working with cryptographic keys:

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| agency | we manage our keys | computers manage our keys for us |

| scope | individual humans or entities have keys | devices have keys |

| visibility | our keys are visible to us | we never see our keys |

| sharing | we explicitly share our public keys with other humans | our devices share public keys with each other as needed |

| stability | keys are stable components of identity, like email addresses or phone numbers; we generate them once and provide the same private keys to multiple applications on multiple devices | keys are created for us as needed on each device by each application; they never leave that device, and are never shared with another application |

| examples | PGP, various forms of corporate or governmental PKI | WhatsApp, Signal, Telegram |

| my take | never really took off | seems more promising |

TOFU considered squishy. Image: Yoav Aziz

TOFU and other meat substitutes

WhatsApp, Signal, and others solve the problem of associating public keys with identities using an approach called “Trust on First Use”, or TOFU.

Here’s the idea behind TOFU:

- When Alice invites Bob to communicate with her, she just trusts that the first person to show up saying they’re Bob is, in fact, Bob.

- Bob and Alice exchange their public keys on that initial connection.

- From that point on, and on subsequent connections, they can use those keys to authenticate and encrypt messages to each other.

It seems safe enough to trust just that one time that Bob isn’t being impersonated. After all, what are the chances that an adversary would know that Alice was going to invite Bob at that precise moment, and would manage to show up before Bob himself did? Anyway in most scenarios, the worst that could happen is that the real Bob shows up after the fake Bob, and Alice realizes that fake Bob fooled her and is able to straighten it out.

The problem, though, is that the “first use” bit is kind of misleading, because in practice TOFU doesn’t happen just once.

To understand why, it’s worth clarifying that when we say “Bob” or “Alice” we should really be

saying Bob's iPhone 10 or Alice's new Dell laptop. As the table above makes clear, these keys

don’t pertain to the individual, they’re created by a particular application on a particular device.

So what happens when Bob gets a new phone, or Alice reinstalls the software on her laptop?

What happens is an “account reset”, and at that point we’re back to TOFU — except that now, the attack scenarios are a bit more plausible: an impostor might have engineered the reset, and it would be more feasible to exploit it.

And although a reset might not happen that often for any given individual, as the number of participants goes up so does the frequency of resets. From the Keybase blog:

In group chats, the situation is even worse. The more people in the chat, the more common resets will be. In a company of just 20 people, it’ll happen every 2 weeks or so, from our estimate. And every person in the company will need to go meet that person. In person. Otherwise, the entire chat is compromised by one mole or hacker.

I’ve lifted a technique from Keybase that they call a Seitan token exchange — the idea being that Seitan is tougher than TOFU, I guess? Image: Sigmund

Introducing Seitan

In the article quoted above, the Keybase team makes the case against TOFU and present their

solution. I’ve stolen adapted yet another idea from Keybase: They call their invitation protocol

the Seitan token exchange; it adds a secret key

to the invitation process in order to avoid the repeated leaps of faith required by TOFU.

Here’s how it works:

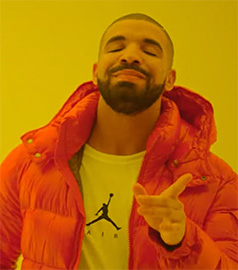

Rather than invite Bob and then accept the first person who shows up saying they’re Bob, Alice gives Bob a secret invitation key when she asks him to join the group.

We could just store that secret key on the signature chain, and ask Bob to repeat it back to us when he’s ready to join the group. But we’d prefer not to store unencrypted secrets on the signature chain. Remember, everyone in the group gets a full copy of the chain, so so everything in it is “public” within the group. Although we generally trust members of the team, we’d rather not make it possible for another member to co-opt Bob’s invitation and impersonate him.

By including a single-use secret code in an invitation, we can make the process of adding members to our team more secure, without introducing complexity or crypto mumbo-jumbo.

So rather than use the secret key directly, we use it as a seed to generate a single-use keyset, with public and private signature keys. Here’s how that works:

Alice generates a secret invitation key and gets it to Bob, perhaps by emailing him a special invitation link.

Alice uses the secret key to generate a keyset. She adds an invitation entry to signature chain, containing the public signature key from that keyset.

On Bob’s side, he uses the secret key to independently generate the same signature keypair. He uses the private key to sign a document that serves as proof of invitation.

Now Bob can show that proof to any other group member — it doesn’t have to be Alice, or even an admin — and they’ll have all the information they need to confirm that this is indeed the Bob that Alice invited.

As soon as Bob joins the group, the first thing he does is to generate a new random keyset, which will replace the ephemeral ones generated from the invitation key. He posts the new public keys on the signature chain.

Now anyone in the group who wants to know Bob’s public keys can get them from the chain. (Alice’s public keys are also in the chain, in the root link.) Et voilà: No key parties, no PKI, no TOFU, and yet we’re off to the races with public-key encryption.

If you’re very sharp, at this point you might be thinking that I’m trying to pull the wool over your eyes by using a not-so-secure channel to bootstrap a secure one.

I hope you’ll at least grant me that if Alice wants to collaborate with Bob using our shiny new local-first software, at some point she has to communicate with him using some other channel, if only to send him a URL or tell him what to install. It’s a small step from there to include a secret key in the URL.

If this is a high-stakes scenario where we’re targeted by active adversaries, we’ll want to be very careful about using a trusted encrypted channel to send the invitation.

In most cases, though, something like email or text is “secure enough”. Keep in mind that this pre-existing side channel just needs to be trusted for as long as it takes Alice to invite Bob and for Bob to use the invitation to join. Once that’s happened, the secret key is of no use to anyone else.

3. Peer authentication

How can we be sure who we’re talking to?

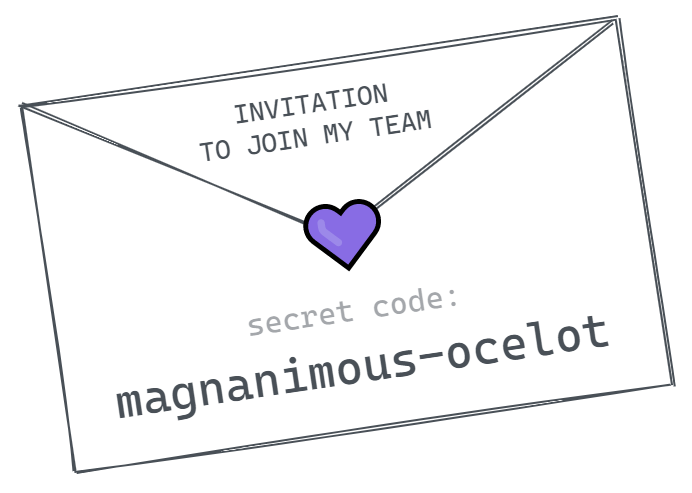

Q: Without a server to vouch for his identity, how does Alice know it’s really Bob at the other end?

We’ve solved the problem of verifying Bob’s identity the very first time he shows up to join the team. But that’s a one-time thing. How are we going to authenticate Bob the rest of the time?

When I log on to Trello, I know it’s really Trello on the other end because I typed in trello.com.

Trello knows it’s really me because I logged in with my email and the password they have on record

for me.

When someone tries to connect directly to Alice’s computer, saying they’re Bob, how does Alice know it’s not an impostor — Eve, for example?

The most straightforward solution I’ve found here is a signature challenge.

This isn’t the exact protocol, but it gives the basic idea.

Alice knows Bob’s public keys, because he put them on the signature chain when he joined. Using his public signature key, she can validate Bob’s signature of any message. So we just need to get Bob to sign something.

Bob could just show up with a signed message that says Hello I am Bob. But possession of a

signed document isn’t enough to prove that he’s Bob — if that was the case, anyone Bob

authenticates to could just keep a copy of that signed message around and use it to impersonate

him.

We need to know that maybe-Bob is signing something now, on demand, rather than handing over a document he already had. So we need to make sure that the message they’re signing is unique and unpredictable: Maybe-Bob should have no way of knowing what the message will contain.

That means that we need a multi-step protocol in order for Alice and Bob to authenticate each other.

Here’s how this works in @localfirst/auth:

- Bob connects to Alice, and sends an identity claim asserting that he is Bob.

- Alice responds with an identity challenge — a message that includes Bob’s identity claim, and adds to it a timestamp and a random nonce.

- Bob responds with an identity proof — a digitally signed copy of the challenge.

- Alice validates Bob’s signature against the original challenge message, using Bob’s public signature key. If it checks out, she responds with an identity acceptance message indicating that she’s convinced of Bob’s authenticity.

4. Read authorization

How to share data while also hiding it

Q: How can you keep some users from seeing sensitive information if each user has a complete copy of the data?

When a server doesn’t think you should see a certain bit of data, it simply doesn’t let you have it.

In a peer-to-peer application, we generally replicate the same database across all users. But what if there is sensitive data embedded alongside less-sensitive data? For example, suppose you’re working with a staff database: Along with names and addresses and phone numbers that everyone can see, you have things like salaries and social security numbers that only authorized members can see.

As I’d hope you would already have guessed at this point in this article, the answer has to do with encryption: We want to encrypt sensitive data in such a way that authorized members can decrypt it, but others can’t.

But how can we encrypt something once so that multiple people, each with their own keys, can decrypt it?

If you’ve ever rented a vacation home or apartment, you might have run into one of these. A lockbox

allows you to use one key (or code) to unlock another, which you can in turn use to unlock the thing

being secured.

The idea of using encryption keys to encrypt other encryption keys is by

no means original, but as far as I can tell no one has given this technique a catchy name. Let’s

see if we can make the lockbox metaphor a thing!

Introducing the lockbox

One solution would be to encrypt the sensitive data itself multiple times, once for each person who is allowed to read it. But this would be inefficient, especially if we were encrypting a lot of data.

A better solution is to encrypt the data itself once, with a single key, and then encrypt that key multiple times, once for each reader.

I call an object that contains an encrypted key a lockbox, by analogy with the handy device used to lock up keys in a public place for real estate agents and vacationers.

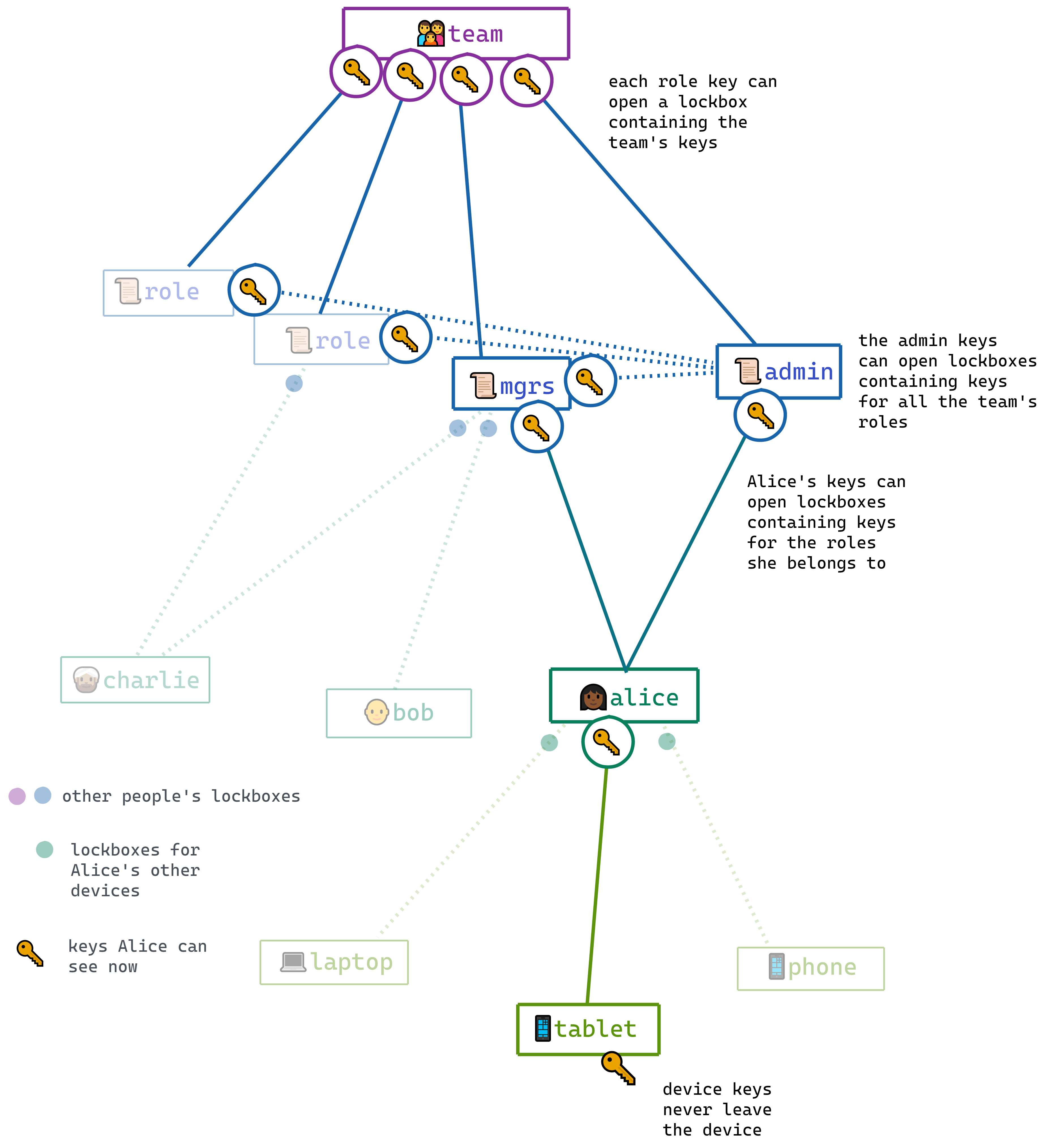

To make this easier to reason about, in @localfirst/auth we associate read privileges with

roles. Each role has its own keyset, and each member of that role has a lockbox containing that

keyset that only they can open.

In addition to that, we have a team-wide keyset, and we make a lockbox containing that keyset for every member as well.

Just like a homeowner or apartment manager can put a lockbox out in public, we can put these lockboxes right on the signature chain along with everything else. It’s a beautiful thing.

User keys and device keys

So far I’ve been kind of vague about the distinction between user keys and device keys, and this is a good time to clear that up.

Device keys are generated randomly on each device, and their secret parts never leave the device.

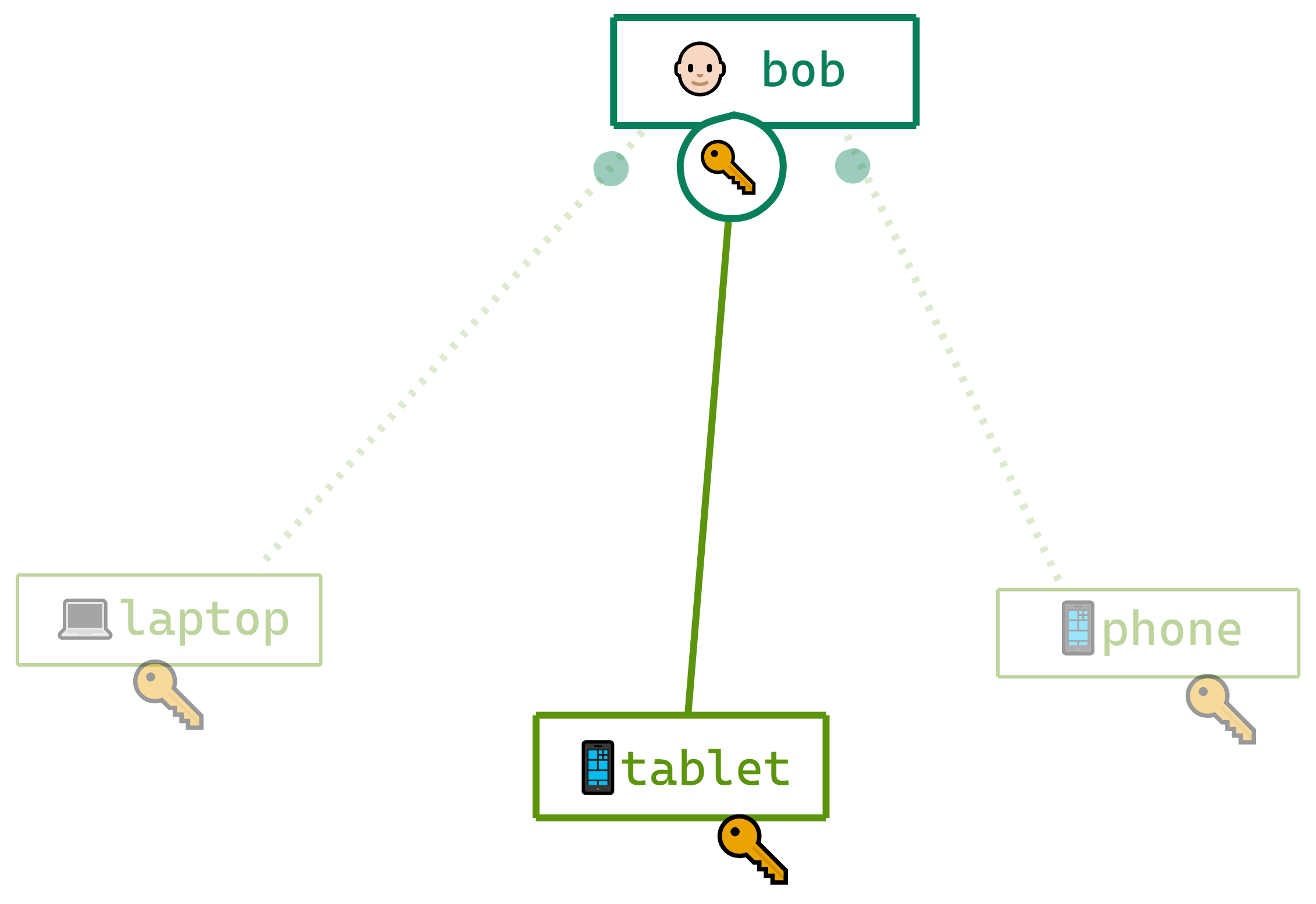

User keys are generated randomly on the first device that a person uses to connect to the team. Every time a user adds a new device, we make a lockbox for that device containing their user keys, and we put that lockbox on the signature chain.

When two devices connect, they actually authenticate to each other as devices, not as users. So Bob

tries to connect with Alice, his identity claim is not Hello I am Bob but Hello I am Bob's laptop

or Hello I am Bob's Galaxy S27; and he signs the identity challenge with his device keys, not with his

user keys.

Each of Bob’s devices has its own key, and obtains Bob’s user keys via a lockbox.

But Bob’s privileges within the group pertain to him as a person, not to his individual devices. You might notice that there’s a graph emerging here: A team has one or more roles; each role has one or more members; and each member has one or more devices.

The key graph and key rotation

This idea of a graph, with keys as nodes and lockboxes as edges, becomes very useful when we turn our attention to the problem of rotating keys.

Keys provide access to other keys, via lockboxes; so we have a graph where keys are nodes and lockboxes are edges.

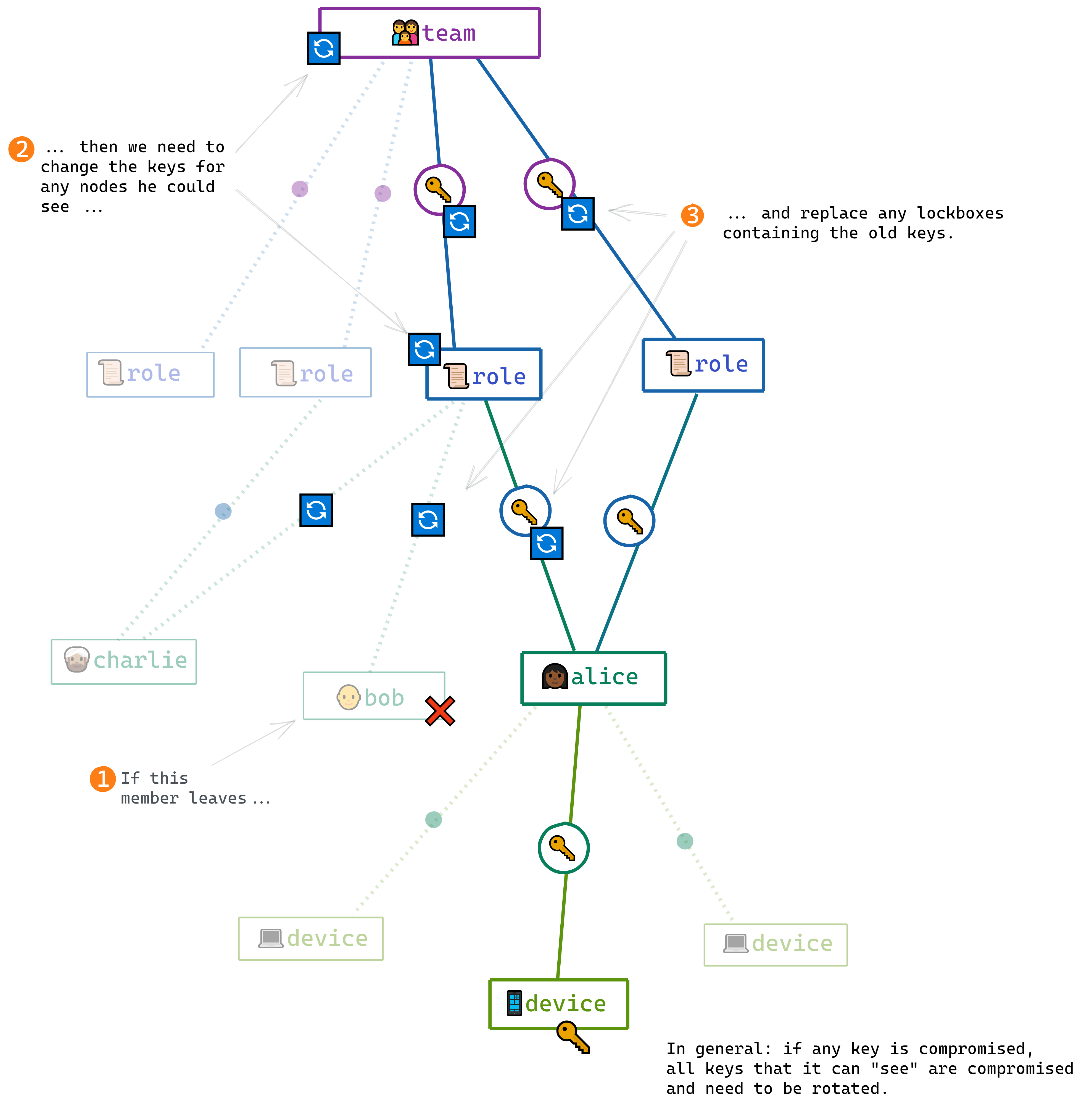

If Charlie is removed from the team, we need to replace the team keys, because he had access to them. If he was an admin, we need to replace the admin keys; and if he belonged to any other roles we need to replace those role keys as well.

If Bob loses a device, we need to treat his old device’s keys as compromised. His device keys had access to his user keys, so we need to treat those as compromised as well; and so on up the chain to any role keys he had access to, as well as the team keys.

When a member leaves a team or a role, or a device is lost, we say the corresponding keyset is “compromised” and we need to replace it — along with any keys that it provided access to.

5. Write authorization

“Don’t trust the client” when there’s nothing but clients

If you’ve ever created a traditional web app, you probably learned early on that you can’t trust what’s coming from the user’s browser.

You have no control over what happens “on the client” — you might think it’s your code, but it’s on someone else’s hardware. A malicious user could be running a modified version of your web app, or could be tampering with the data that it sends your server.

So it’s not enough to implement permissions on the client. Suppose your app checks whether a user has permission to modify a certain field; it’s not enough for the app’s UI to stop them — you still have to check their updates when they get to the server, to make sure they haven’t bypassed your rules by tampering with the payload.

In a peer-to-peer world, there’s nothing but clients — so you can’t trust anyone. That means that every peer needs to check the information they get from other peers against the team rules. A traditional web app can just assume that whatever the server tells them is legit; a peer-to-peer app can never let its guard down and has to treat every bit of data it gets as potentially malicious. So every client has to know what the rules are, and enforce them with every message received.

What happens if a rogue peer sends changes that break the rules? Everyone else simply ignores them, the same way the server would ignore illegal changes from a rogue client.

Tired: Permission

Wired: Attention

This requires another inversion of our usual thinking. Is permission the right word for what we’re thinking about? After all, our peers don’t need our permission to do whatever they want on their own devices, right? Bob has a full copy of the team’s data on his device, and we can’t stop him from, say, adding a zero to his own salary.

What we do have control over is whether we pay attention to Bob’s change.

Rather than having a central authority enforce your rules, and then passively accepting anything blessed by the server, we all have to continuously enforce the rules by choosing who we will listen to and who we will ignore, and which changes we will accept and which ones we will disregard.

Each user has the full signature chain and can use it independently to compute the correct current state of the group’s membership and permissions. So each user can independently determine whether or not to accept another member’s changes as valid. If the signature chain says that Bob can change salaries, then we accept his change. If not, we don’t.

6. Synchronization and concurrency

Having solved all of these thorny problems, all we need to do now is make sure that members can connect and sync up their signature chains. I figured this would be, as they say, a simple matter of programming.

As it turned out, I stalled out quickly after I started working on this. I just could not wrap my head around these questions:

- Concurrency: How do you merge divergent signature chains?

- Conflicts: How do you deal with concurrent membership changes that are logically incompatible?

- Protocol: What actually takes place, in what order, when two peers attempt to connect?

Dealing with concurrency

The first thing that I got stuck on was how to deal with concurrent changes. If Alice and Bob are both offline and both make changes to the signature chain, then how do you merge their two changes to end up in a consistent state?

After all, we’ve gone to a lot of trouble to ensure that you can’t retroactively modify the chain, what with the “hash-chaining” and the “cryptographic signatures” and all.

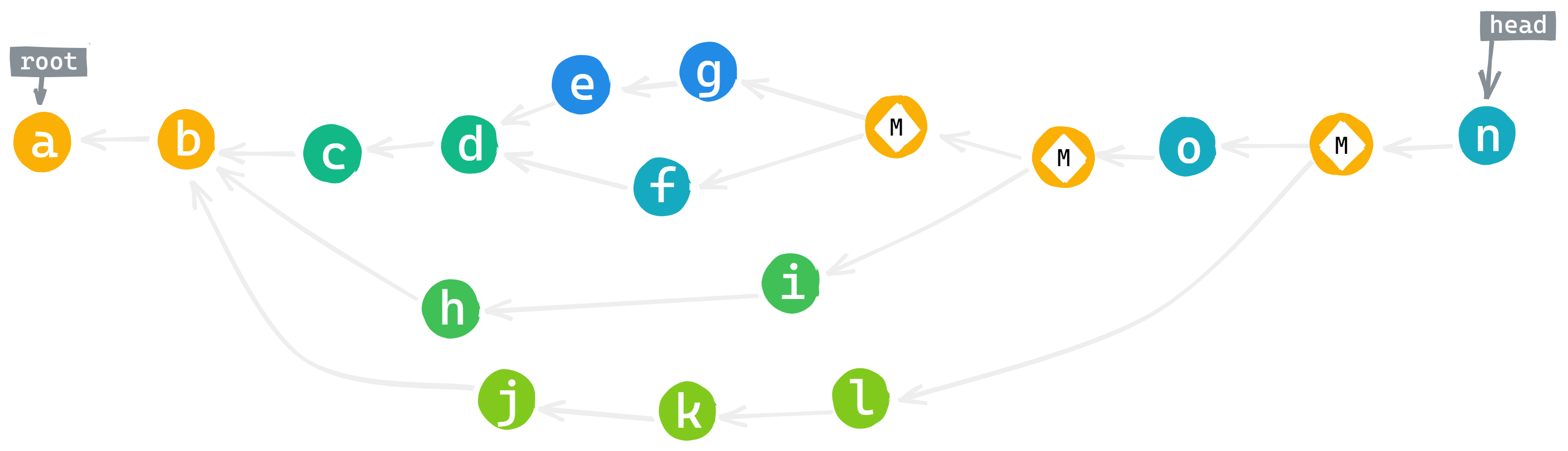

Here I eventually took inspiration from Git, which is also a decentralized collaboration system built on top of an append-only hash-chained data structure.

When you’re working alone on a Git repo, your chain of commits is very reminiscent of the signature chain we’ve described so far. Once you start working with two or more collaborators, though, you introduce the possibility of branching and merging.

Nothing is “merged” in a literal sense. Rather, Git adds a special merge commit that is hash-chained to two prior commits rather than one. That’s why Git commits form a graph — specifically, a directed acyclic graph (DAG) — rather than a one-dimensional hash chain.

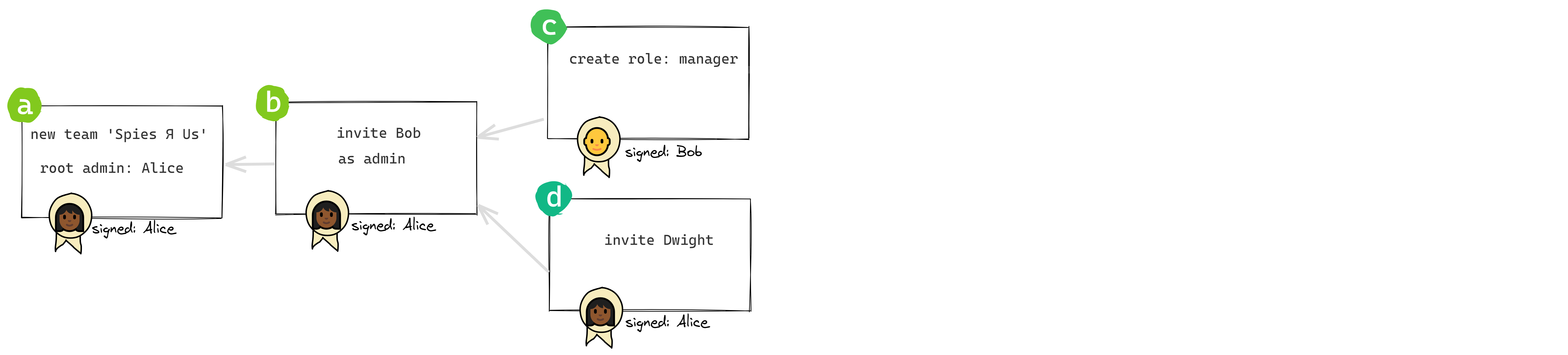

So internally our signature chain needs to become a signature graph (although out of bloody-mindedness we’ll keep calling it a chain). This means that multiple links can have the same predecessor:

Also, we’ll need a new kind of link as a marker for merges. The merge link’s only content is a pair of hashes, one for each of the branches being merged. It has no author and no signature.

Resolving conflicts

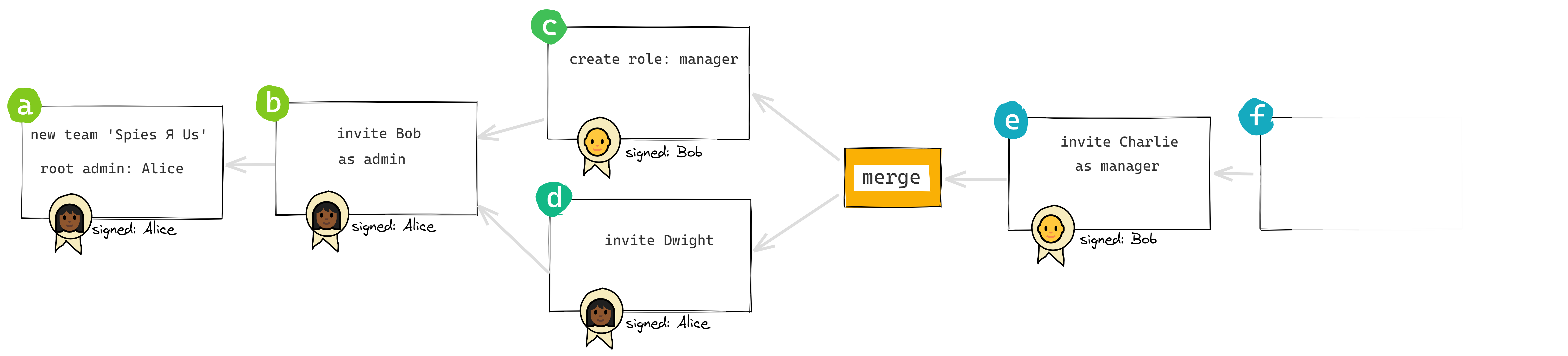

In the divergence illustrated above, there’s no conflict between the concurrent actions. These two actions could be applied in any order, and the result would be the same:

👨🏻🦲 Bob creates a

managerrole

👩🏾 Alice invites 👴 Dwight

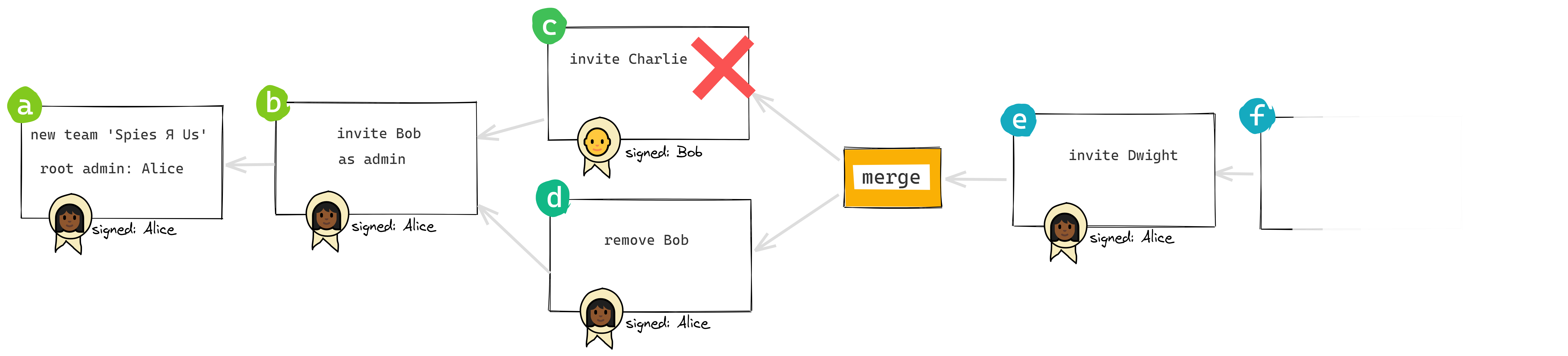

But suppose we had these two concurrent actions:

👨🏻🦲 Bob invites 👳🏽♂️ Charlie

👩🏾 Alice removes 👨🏻🦲 Bob

If we apply these two actions in the order they’re shown, there’s no problem. But if we apply them in the opposite order? Problem. Bob can’t invite Charlie if he’s been removed from the group.

As luck would have it, right around the time I was struggling with this, Martin Kleppmann sent me a pre-publication draft of a paper he was working on with Matthew Weidner et al. that formalized a way of dealing with this very problem: “Key Agreement for Decentralized Secure Group Messaging with Strong Security Guarantees“.

Much of this paper goes over my head. However, the scenarios they consider jumped out as being exactly the sort of thing I was wrestling with:

- Two group members A and B concurrently remove each other. Do the removals both take effect, cancel out, or something else?

- While group member A removes B, B concurrently adds a new group member C. Should C be in the group?

- A group member A is concurrently added and removed. This can happen if A is initially in the group, one member removes and then re-adds A, while concurrently another member only removes A. Should A be in the group?

Weidner et al. describe the general concept of a decentralized group membership (DGM) scheme, which defines how these sort of conflicts are resolved; and they propose a particular one that they call the strong-remove DGM scheme, reasoning as follows:

It is easy to re-add a group member who has been inadvertently removed, but it is impossible to reverse a leak of confidential information that has occurred because a user believed to be removed was, in fact, still a group member. …

In the design of our DGM scheme we are guided by one observation: a user who is being removed from a group should not be able to circumvent their removal.

In general, then, removals always win in the case of conflict. I’ve interpreted this broadly to mean that if Bob is being removed from the group, any actions he takes concurrently are disregarded.

That leaves mutual removals (scenario 1 above):

👩🏾 Alice removes 👨🏻🦲 Bob

👨🏻🦲 Bob removes 👩🏾 Alice

Alice is offline on a plane, and she removes Bob from the group. Down on the ground, Bob removes Alice from the group. When Alice lands and gets back online, who’s still in the group?

Mutual removals are actually a special case of circular removals, with N of 2. We also need to consider situations with N of 3 or more — for example:

👩🏾 Alice removes 👨🏻🦲 Bob

👨🏻🦲 Bob removes 👳🏽♂️ Charlie

👳🏽♂️ Charlie removes 👩🏾 Alice

Here the paper’s ruling is to throw all the bums out: Everyone involved in this kind of circular firing squad ends up dead.

Of course, this way you can easily end up with a group with no members. While that might very well be the correct outcome in this bizarre scenario, I chose to avoid it by taking seniority into account to resolve mutual removals. If Alice and Bob concurrently remove each other, and Alice was added to the group before Bob, then Alice stays and Bob is out. (And of course if Alice created the group, she always wins.)

Flattening the graph

When we resolve logical conflicts like this, we don’t actually remove any actions from the graph; and when we merge two concurrent branches, we don’t actually move the individual actions around. They all need to be there, in their original positions relative to each other, to preserve the verifiable integrity of the whole thing.

When you add a link to the signature chain, it’s checked for validity based on the known state of the group at that time. For example, if Bob removes Charlie, Bob needs to be an admin at that time. If he isn’t, the action of removing Charlie is never added to the chain. If he is, it’s added and will remain on the chain forever.

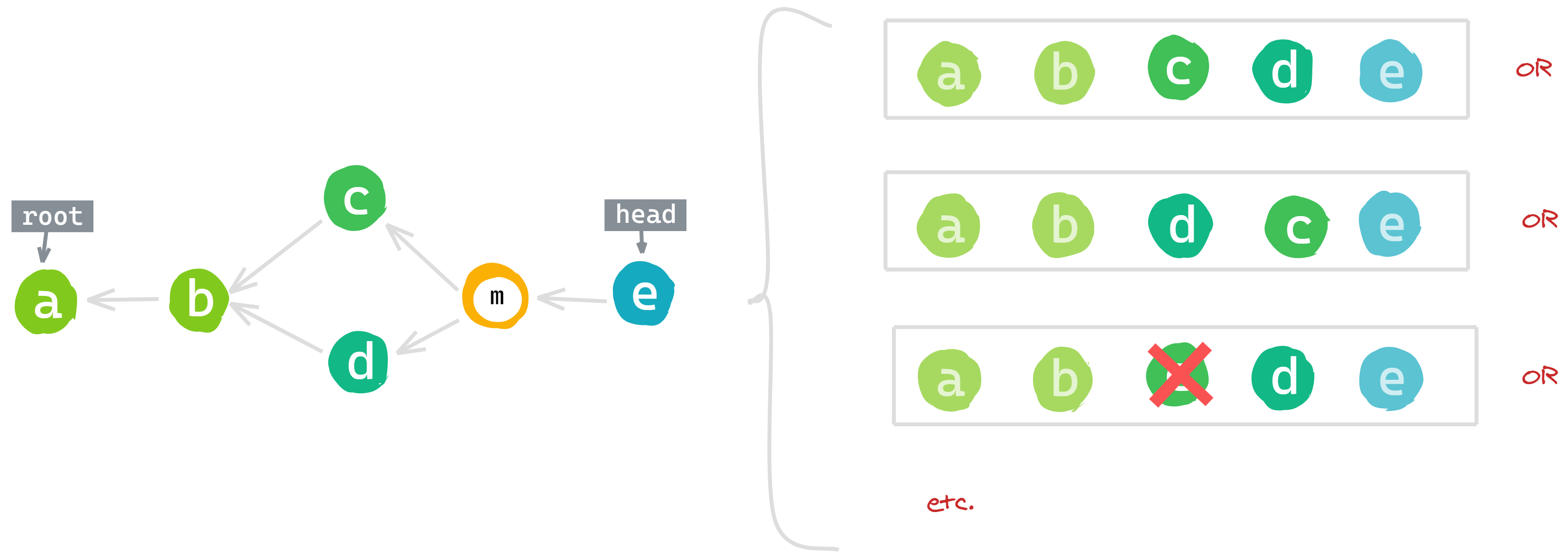

In order to calculate the current state of the group, we first need to come up with what’s called a topological sort of the signature graph — meaning, we need to flatten the graph back into a one-dimensional sequence.

To do this, we’ll need to recursively resolve each pair of branches into a single sequence, until the whole graph has been flattened. To do that, we need to decide how to order the concurrent actions, and we might also need to filter out actions that are ruled out by our strong-remove logic. Importantly, anyone doing the calculation needs to be able to independently come up with the same answer.

Note that when you merge two branches, what you end up with is no longer a hash chain, and that’s fine. Before we flatten it, we’ll have checked the integrity of the whole graph by verifying its hashes and signatures. Once that’s done, we can choose which nodes, and in what order, we’ll use to compute the group state.

As it turns out, once you’ve done the filtering, the ordering doesn’t much matter for our purposes. So we choose one or the other of the two branches to go first in an arbitrary but deterministic way, to ensure that everyone arrives at the same ordering.

On the left, we have a graph where actions c and d take place concurrently. Depending on the rules we use for ordering and filtering, this graph might be flattened into any of the sequences shown on the right.

Synchronizing

Whenever we connect with another peer, we’ll want to sync up our signature chains.

Would you believe it, no sooner had I mentioned this to Martin Kleppmann than he sent me another paper in prepublication that was directly applicable to my problem: “Byzantine Eventual Consistency and the Fundamental Limits of Peer-to-Peer Databases“, co-written with Heidi Howard.

Conclusion: When you’re stuck on a software project, ask Martin to send you whatever research he has in the pipeline.

As the title of their paper suggests, Kleppmann & Howard are working on a more difficult overall question, the details of which I won’t claim to understand. But as it happen they end up needing to do exactly the same thing I do, which is to reconcile directed graphs from two peers, over the wire, as efficiently as possible.

At this point the data structure containing our signature chain-graph-thing might look something like this:

{

root: 'awfLr',

head: 'ZDoRu',

links: {

'awfLr': {...},

'GpLPr': {...},

//...

'ZDoRu': {...}

}

}

The keys here (awfLr etc.) are the hashes of the corresponding nodes in the signature chain.

Our task is for Alice and Bob each to figure out what links the other might be missing, without shipping the entire chain.

We can quickly find out if our chains are at all different just by comparing our head hashes: Two

chains with the same heads are guaranteed to be identical.

If our heads are different, we could just progressively exchange the most recent N hashes, until

we figure out where we diverged. But that’s a lot of back-and-forth. Kleppmann & Howard propose a

sexy way of cutting down on the round trips, using a probabilistic device called a Bloom

filter.

… TODO

7. Connection protocol

Nothing is easy

Finally, finally, all these pieces need to be tied together into a coherent whole that allows people to invite their peers to collaborate, and then connect securely. Surely this piece is straightforward, right?

Well.

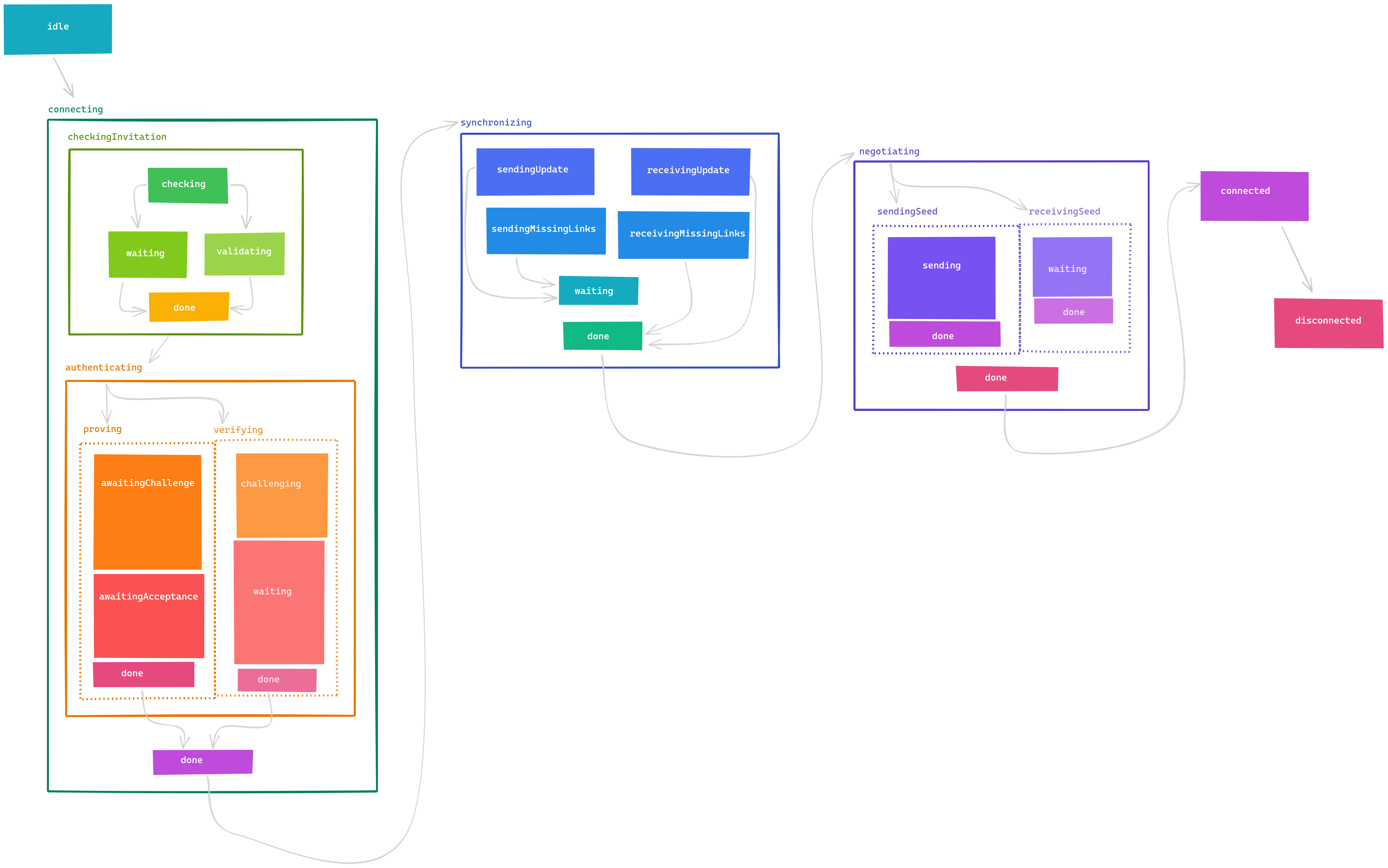

Let’s just say that there are a lot of moving parts here:

- Handling invitations: If one of the devices belongs to someone trying to join with an invitation, then we need to validate the invitation.

- Mutually authenticating: If both devices belong to members, then each one needs to simultaneously challenge the other’s identity and prove their own identity.

- Synchronizing: Once everyone has been authenticated, we need to update each other’s signature chains with the latest actions on either side. Once we’re connected, we need to keep watching for any new changes to the signature chain, and update each other as needed.

- Key agreement: Finally, the two peers needs to agree on an encryption key for the application to use to communicate.

I didn’t get very far into coding the connection protocol before I realized that the complexity was going to outpace my cognitive abilities if I didn’t do something to contain it; and that something was to finally take a deep breath and learn how to work with a finite state machine.

It’s a good thing, too. The buggiest code you’ve ever had to work with, that mind-bending inception of nested if-thens and switch statements, is probably code that should’ve been written as a state machine but wasn’t.

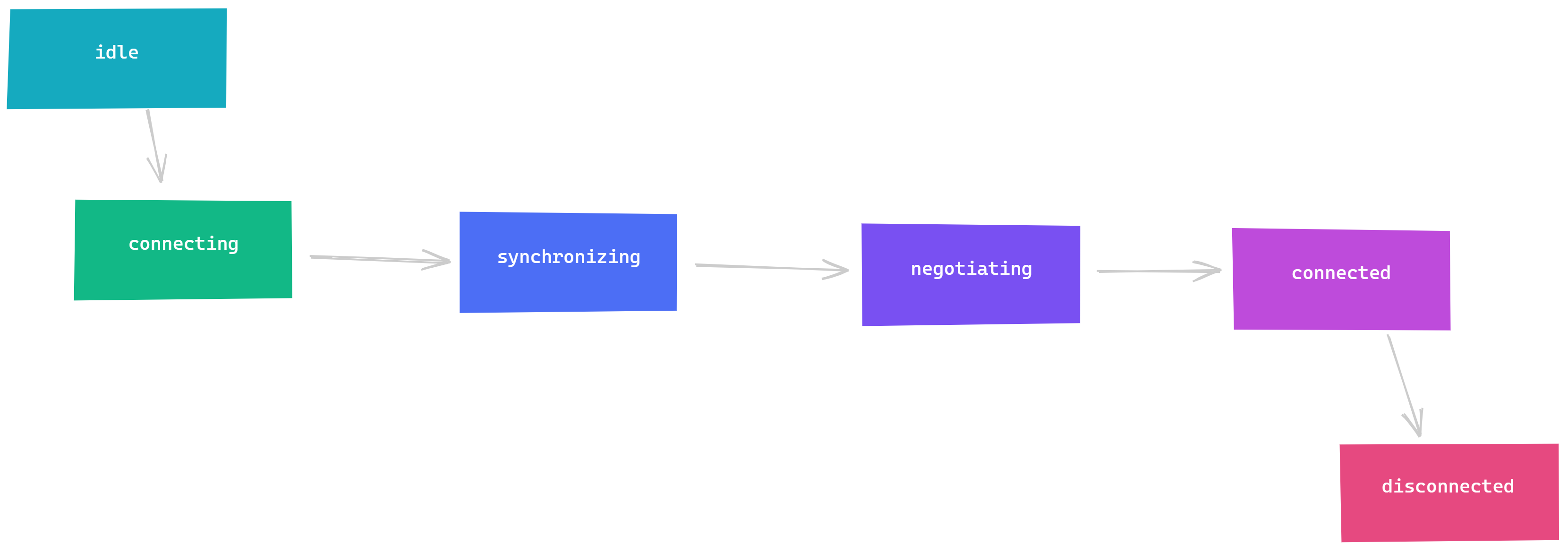

We’ve all been there, and it’s just because things always look simple until you dig in a little bit. In my case, at first inspection it seemed like all I would need was this:

But in reality, this is where I ended up:

As they say, you have a state machine in your code whether you know it or not — the only question is

whether you make it explicit or not. And making it explicit is doubly important in this context:

Some of the most consequential security-related bugs were the consequence of implicit state machines

that allowed attackers to sneak into states that should have been impossible. TODO examples?

In the end, it seems clear that the time invested in learning to use state machines, and XState specifically, has paid off in the form of code that I’m able to reason about even when my brain is weak and foggy.

Introducing the @localfirst/auth library

I’ve been working on this for nearly a year now, and I’m excited to finally have a beta release of

the @localfirst/auth library.

etc

etc

TODO

I’m finishing up work on a simple chat application that demonstrates how this library can be used. If you’d like to see that when it’s ready, you should follow me on Twitter: @herbcaudill

Thanks

This project’s shape emerged from a series of conversations early on with Peter Van Hardenberg of Ink & Switch. Peter drilled into my head the idea that device keys should be generated locally and never leave the device, and pointed me towards Keybase’s signature chains. The framing of permission vs. attention is his as well.

As the above makes clear, Martin Kleppmann has been very generous with his time and expertise, and has gotten me unstuck more than once. Martin is the creator of Automerge and co-author with Peter of Ink & Switch’s local-first manifesto. In my experience, 100% of the time he has a PDF up his sleeve that solves your exact problem.